Gardens & Sukiya Living

Japanese gardens attract and intrigue us because they are so different from Western gardens in their design, elements, and purpose.

Those at Yume are configured in eight settings. Each displays a different facet of a 1,000-year-old and still-evolving Japanese art form that strives for a balance of natural and man-made beauty. It is a tradition that shows profound respect for wildness even while gently reshaping it into idealized landscapes that lead us to reflect on our response and relationship to nature.

The Modern Garden

This courtyard garden is contemporary in tone and contains fine gravel and granite, the principal elements of a Japanese modern garden. Slabs of granite and squares of dark slate are distributed in a graphic design and are surrounded by the fine white gravel, kept diligently swept to remove all traces of intrusion by wind, raindrops, or animals, and to reflect another guiding principle in certain eras of Japanese garden design, the aesthetic of paucity or yohaku-no-bi, literally “the beauty of extra white.” A sculptural element is a common central accent in this kind of garden.

The Residential Courtyard Garden

This style, called tsubo, is embodied in tiny private gardens still found inside or at the rear of traditional residences in the old Japanese imperial capital of Kyoto. The two examples at Yume are partially enclosed by bamboo fencing and in the tradition of their kind, they are meant for viewing and not to be actually entered. In one, small and smooth gray stones underlay a weathered round water basin set amid shrubs; in the other, a vertical basin perches atop a rock, sharing the space with a stone lantern. Were you in your Kyoto home, you would gaze on your compact garden from a floor cushion in the interior of the house, the scene framed by opened sliding shoji doors, creating the sensation of viewing a painting or a stage set. At Yume, this view is afforded by machiai. These are traditional covered waiting benches constructed with clay walls, cedar-shingled roofs and wooden posts and beams, and serve as viewing shelters from which to enjoy the gardens.

The Karesansui Garden

A favorite Japanese garden type is the dry landscape arrangement, or karesansui. It can include raked sand, pebbles or gravel, large stones and small pruned bushes and trees, carefully composed to form a miniature stylized scene of nature. This concept derives originally from China, and was later influenced by the Japanese monochrome ink landscape paintings (sumi-e). The Karesansui Garden at Yume utilizes three rock groupings anchored on large vertical stones, surrounded by whitish-grey gravel, evoking the remembered image of peaks rising above clouds. The stones are from the nearby Santa Catalina Mountains, in accord with the Japanese custom of landscaping with local materials. The garden is situated so that in winter, when intervening trees have dropped their leaves, the mountains can be seen in the background. A natural view beyond a garden that is incorporated into its design in this way lends a small garden depth and is called “borrowed scenery.”

The Dry River Garden

A rock garden arrangement often seen in Japan is that of a metaphorical river. The Dry River Garden at Yume springs from its birthplace in mountains, symbolized by large vertical rocks at the head of the waterway. As the stream bed meanders downward in gentle curves, it widens in the bends, as it would in nature. A mix of real river rocks mimics the rock-moving abilities of an actual stream: small tumbled gray river rocks of uniform size pave the bottom of the stream bed, and stones that are too large for the “current” to move remain in the middle of the stream. Completing the illusion of flowing water, a wooden footbridge across the lower end of the river leads visitors to the next garden at Yume.

The Zen Garden

A major influence on Japanese garden design has been Zen Buddhism. Its main spiritual practice – meditation that bestows inner strength and composure – calls for excluding the superficial from the mind and ornamentation from the environment. The Zen Garden at Yume does precisely that. Its heart is a rectangular bed of gray-white gravel raked into lines and curves to resemble rippling water or waves, and sometimes also heaped into one or more cone-shaped mounds to represent mountains or islands. This is edged with a double border of pale, narrow granite slabs enclosing a contrasting surround of water-worn dark gray beach cobbles.

The Koi Pond Garden

Yume’s most popular garden has as its focal point a large koi pond. In spring, summer and fall green lily pads float on its surface, bearing delicate pink and white flowers, and year around red-and-white Japanese carp swirl through its waters and around a half-submerged rock representing an island in what is a metaphor for an inland sea. Other rocks jut into the water like promontories and rise above the “shoreline” like headlands; still more are heaped like low mountains, down which water flows into the pond in a murmuring cascade. More than any other of our gardens, the Koi Pond Garden is designed to give casual pleasure, and a path winding beside the pond provides entertaining shifts in viewing angles. The veranda of a waterside pavilion extends over the water, providing a platform from which to spy on the flashing fish that congregate below to be fed.

Tea Ceremony Garden

Roji means “path,” and in particular the approach to a tea house. For lack of space, Yume’s Roji Garden has no tea house, but other key elements of the subdued and often almost woodsy setting associated with tea houses are here. Irregularly shaped natural stepping stones wend to a basin carved into a dark gray boulder; the sound of water falling into the cut stone from a bamboo pipe suggests the gurgle of a forest stream, and the overflow makes the sculptural boulder glisten like a wet river rock. A bamboo ladle atop the boulder is for dipping water to ritually cleanse one’s hands and mouth before entering a tea house. Softening the surrounding space are the curly stems of groundcover plants, and small trees and shrubs shade the area with branches largely left untrimmed to create a shadowy atmosphere that calms the mind and spirit in preparation for a tea ceremony. The Roji Garden is the smallest garden at Yume, but compressed in it is the sensory experience and spiritual passage of a walk from a bustling day-to-day world to the repose of a secluded hut to take part in the ceremony called Chado, “The Way of Tea.”

The Bamboo Garden

In planted Japanese gardens, trees – including bamboo – are the most important vegetation. They help structure and frame space, a role clearly played by the bamboo that towers beside a path of packed earth running through this garden at Yume. Entry is through a 10-foot-high wooden gateway roofed with tiles. Much taller at 30 feet is the bamboo bordering both sides of the path. The passageway is broad, but the height of the supple bamboo stalks makes their tops bend and mingle in a leafy canopy arching over the full width of the path. The effect is of strolling through a cloistered natural grove, and the pale green bamboo trunks – some thick, some thin – form a refreshingly varied visual curtain. Such corridors of bamboo often form the approach to Japanese shrines, guiding the eye to the temple entrance.

The Japanese Architecture At Yume

By showcasing intimate courtyard gardens instead of expansive landscapes, Yume stands apart from nearly all its kindred in North America. In its structures, the focus at Yume is also deliberately different. It centers on a Japanese architectural style called sukiya, chosen for its openness to nature and because it does not intrude upon or interfere with the subtle scale relationships found in our gardens. It complements them, instead.

One key element of the sukiya style is that it opens interior spaces to outside gardens. This creates the feeling of being out of doors even while actually inside. The essence of the style also lies in the pleasing simplicity to be found in using common materials in a refined way. This can be seen in the thick tree branches used as posts in one of the machiai or viewing shelters for contemplating the residential courtyard gardens at Yume. They are peeled of bark and not planed, to expose the beauty of their hidden mottling and markings.

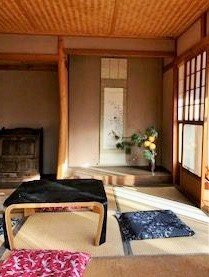

Within Yume’s replica of a traditional Japanese cottage, overlooking the Zen Garden, is another such post. Gently sinuous, it has a natural polish. This pillar lends proportion to a neighboring alcove called tokonoma, devoted to displaying a single traditional Japanese flower arrangement or a hanging scroll with a painterly nature scene or the bold black brushstrokes of a famous poem.

Seating in the cottage is provided by four tatami, heavy mats woven of fragrant rice straw set into the floor, while the ceiling is formed of panels woven of wide strips of bamboo. On two sides of the cottage are pale tan walls, plastered with clay mixed with finely shredded straw, creating a texture that pleases both the eye and the fingertip. On the remaining sides of the cottage are interior shoji doors paneled with rice paper, lightweight for pushing open to reveal sliding exterior doors with glass panels that enclose a small, low veranda. From there it is an easy step down to the Zen Garden directly outside.

The Japanese cottage at Yume is everything traditionally sukiya. It is small, simple and spare, and built of natural materials and with great attention to detail and proportion. This lends the cottage a delicate sensibility and an air of well-cultivated taste, the exact counterpart of the distinguishing qualities of the courtyard gardens at Yume.

Close by the cottage and forming a compound with it beside the Zen Garden is a replica of a small Japanese farm outbuilding. Also built with clay walls and wooden timbers in the sukiya style, on its garden side is an attached and sheltered bench. This is a place from which to contemplate the Zen Garden, or to sit while waiting for a tea master to summon guests to the tea ceremonies sometimes held in the space between the buildings.

Beside Yume’s Koi Pond Garden stands another farm outbuilding typical of the Japanese countryside, adapted to serve as a large viewing pavilion by the addition to it of two low verandas, which overlook the pond on one side and the Roji Garden on the other. Accenting the verandas are sliding shoji doors some 150 years old, from a bygone farm house in the Kansai Region on Japan’s chief main island of Honshu. In another authentic touch, an end wall of the building is plastered in natural clay like its counterparts elsewhere at Yume, and to which a gleaming white lime finish has been applied; such an overcoat is traditionally used to protect the earthen walls of farm storehouses from erosion by rain.